Alexandra Antoine is a Haitian-American artist and educator based out of Chicago. She received a degree in art and art education from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2014. Her work focuses on her Haitian-American identity, which she investigates through language, memory, portraiture, and archival practices. Recently, she has been incorporating Haitian sequins and beadwork into portraitures as a way of holding onto and continuing an art form that is native to her culture. We invited her to Spudnik Press to share more with us about herself and her work.

M Kellman: Can you introduce your artistic practice? What kinds of things are you interested in?

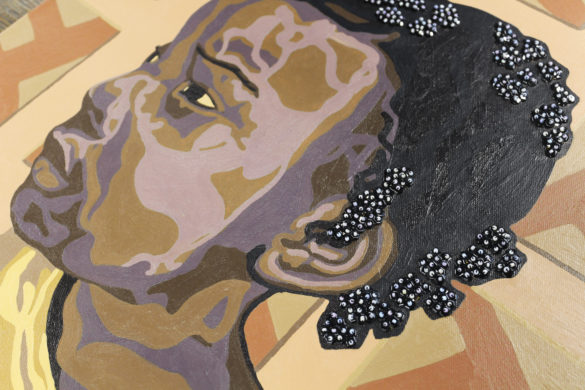

Alexandra Antoine: I am primarily a printer and a painter. I love screen printing and lithography. Fell in love with lithography first time I did it. I’ve always been a painter. While I was at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) I figured out my style of painting. Recently I’ve been incorporating painting along with Haitian beadwork. I like seeing progression, from a beginning stage, middle stage, to the end. It keeps me excited.

I also work on two or three things at a time, so I can swap through different things and then I don’t finish anything too fast. I’ve noticed that in the past few years I really like slow processes.

MK: Are you from Chicago originally?

AA: No, I’m originally from Miami, stayed there till I was 11, then moved to Orlando. I have family all up and down the east coast of Florida. My parents are Haitian, so that’s what lead my parents to go to Florida. I love Chicago! I finished undergrad at SAIC, only planned on staying a year, but then I started meeting other artists, I started teaching and chilling out with the students, and I’m still here in 2019.

MK: Do you think you’d want to end up back in Miami or Orlando?

AA: You know, I thought about it. A lot of my inspiration comes from my culture—when I’m in Haiti, when I’m around family, when I’m listening to family talk. Now, Chicago has a Haitian community but it’s not as tight as New York and Miami cuz those are two hubs where it’s Little Haiti central. Sometimes it gets hard being here, which is why I’ll go see my family in New York often—it’s the closest if I can’t get to Florida. I need to be around the food, around the language—something about being in it helps the gears move.

MK: I notice you incorporate a lot of traditional practices into your work. Can you talk about how you learn these?

AA: I’m really into working with other artisans. Outside of my studio I like to find artists who do things that I wanna learn and learn from them.

When I was in Haiti, one of my friends sat with me and taught me Haitian beadwork. And now I’m working on a piece that’s super big. It’s taking weeks, but I love the process.

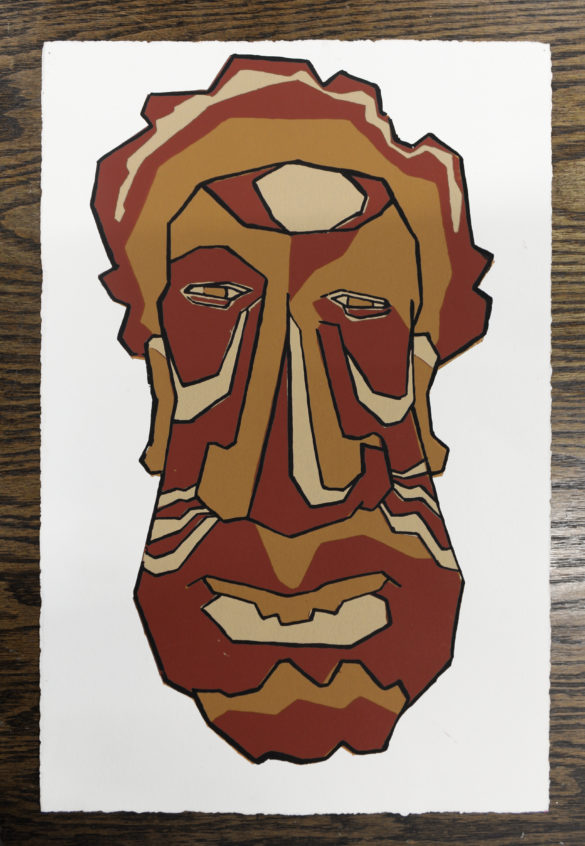

And back in 2010-2011 I went to Mali, West Africa, to learn traditional sculpture. It was just me and my teacher from like 7am to like 8 at night, just hackin’ at wood. I love this because it’s a thing he inherits through his family line. There’s not a syllabus. It’s just “Watch what I do, and you do it”. I love learning like this. The classroom is nice but when you get this one on one, right next to somebody, I like this.

MK: How do you decide which skills you want to learn?

AA: It’s about reconnecting with my culture. I like to choose places within the African Diaspora in art forms that are valuable but a lot of young people aren’t running to learn it. So like my teacher in Mali, if his granddaughter doesn’t want to learn it and he passes, that’s it. Or in Haiti, some of these skills I’m seeing, a lot of older people are doing it, but when you’re gone then who takes it over? I wanna keep these things that could potentially be lost because people migrate or move around.

MK: In addition to your studio art degree, you have a degree in Art Education. Do you teach?

AA: Yes! I’m all about sharing what you know, especially when it comes to African American communities. I was teaching visual arts full time in Chicago Public Schools (CPS) when I got out of school. It’s fun introducing the students to new skills, but what I found was interesting was, when I was in Art Ed and we would go visit schools, I think I maybe saw one black art teacher, if any. And the schools that were all black usually had a white art teacher. African Americans have had a huge contribution to art but none of the students saw teaching art as a career path. I wanted to teach in an all black or predominantly black school because they gotta see that art is a career they can do. And of course when I walk in it was like, “You’re the art teacher?”.

MK: So I imagine you’re not very interested in the traditional Eurocentric art history and art education curriculum, right?

AA: Oh yeah, and that’s where the struggle was. It seems like the way Art Ed is set up in CPS is, “We want you to teach X Y and Z”. But that’s not how artists work. All artists don’t want to just do this one thing this certain way. I took art history in college and it was great learning about da Vinci and Europe and all them, but… We didn’t touch Asia, South America, nothing. And I’m not saying da Vinci and all are not great artists, but what about Faith Ringgold, or Carrie Mae Weems? What about them?

So when I was teaching, I was like, “Let’s get down on the floor”. If an artist was squatting when they do this work, let’s all squat. If they were only using their hands, let’s just use our hands, no paintbrushes, no pencils. Was it what the principal wanted me to teach? Not really. But this is how artists think about the world. We’re not here just to pump out a perfect assignment.

MK: I saw you did some work with Cook County Jail and a juvenile detention center. Does that fit your practice better than CPS?

AA: It does. Right now I’m teaching visual arts with Free Write Arts & Literacy. I came in with the same philosophy—I’m not gonna just teach the fundamentals of shading. There’s so much that the students I work with have experienced, they all come from various communities in Chicago that have their own unique aspects. We can’t just be talking about how to shade. We have to be talking about things that are relevant. And I tell my students, even if you don’t become an artist, this is a way to look at the world differently instead of how you’ve been told to look at the world.

A screen capture from Chi-Raq (2015, dir. Spike Lee). Antoine’s mural can be seen on both walls. Copyright: Amazon Studios, 40 Acres and a Mule Filmworks.

MK: So, a little fangirl moment—Chi-Raq? You painted the mural in the bookstore scene with Angela Bassett. So cool! How did you get that job?

AA: In 2013 I was in a group show at Roman Susan gallery. Then maybe 5, 6 months after the show—I’m teaching at CPS at this point—I get an email from the art director of Spike Lee’s new movie like “Can you come down to the studio and talk about your work?”. So I went down to the space and they told me the concept and gave me some subject matter and said, these are the women we want you to focus on painting. They had me on the set of the bookstore. I was there maybe a month or a couple weeks before they would transform it. The art director let me come on set the day they were shooting in my space. I told my friends—where Angela Bassett takes them into a secret room, all of that is mine.

As an artist, you never know who’s gonna see your work and what that’s gonna lead to. My aim is not always, somebody needs to buy this. You just never know where somebody might see your work.

MK: Did you like the public art aspect of working on the movie?

AA: Yes. It was fun doing that. It was a good experience. I do like it when my work can be accessible to more people than just the art world or just gallery openings and exhibitions. Especially since I work with young people, I want y’all to see there are other ways of being artists. You don’t just have to be in the MCA or the Art Institute. Those are great, but look at your whole community.

MK: Do you have any other instances of showing your work outside a gallery setting?

AA: Yeah, similar to with Chi-Raq—maybe early last year, someone from the Haitian Embassy contacted me and said, “We saw your work at Ghetto Biennale in Haiti and wanted to know if you were interested in a group show at the Embassy in Port-au-Prince as part of the Art in Embassies Program?” Now mind you, I had the Art in Embassies photo on my vision board for the past two years, so when they called I was like, “You don’t have to tell me twice!”. There’s this idea that when people leave Haiti they don’t come back. But I want people to see that us younger Haitian Americans, we always love coming back here.

MK: Any projects on the horizon? Future directions?

AA: This summer I plan to go to Benin. Most Haitians came from Benin, the Congo, Togo, and some parts of Central Africa. There’s an arts and cultural organization in Benin that works with young people, so this summer I’m going to work with them.

In Haiti, people know we come from West Africa—but, with the way enslavement happened, there may be people, especially some of the younger people in West Africa who may not understand how Haiti plays a part in our shared history. I really wanna build relationships with some young folks there, make connections and see what comes out of that.

MK: Could you show me some of your work?

AA: A lot of the people in my work are people I know—either family members, friends, people I met through my travels, but we’ve always had conversations. That’s important for me because I’m showing Haitian culture the way I see it, so I want it to be authentic. To me it’s important to have that relationship, especially if you’re gonna be showing somebody’s image everywhere.

Language, symbols, nonverbal communication, that’s real big in my work. For a while, I was really into scarification practices, because that’s a way of identifying somebody, being a part of a community. When I was in West Africa, my teacher had these three lines—that’s the Bambara tribe. So I was into showing them with these prints.

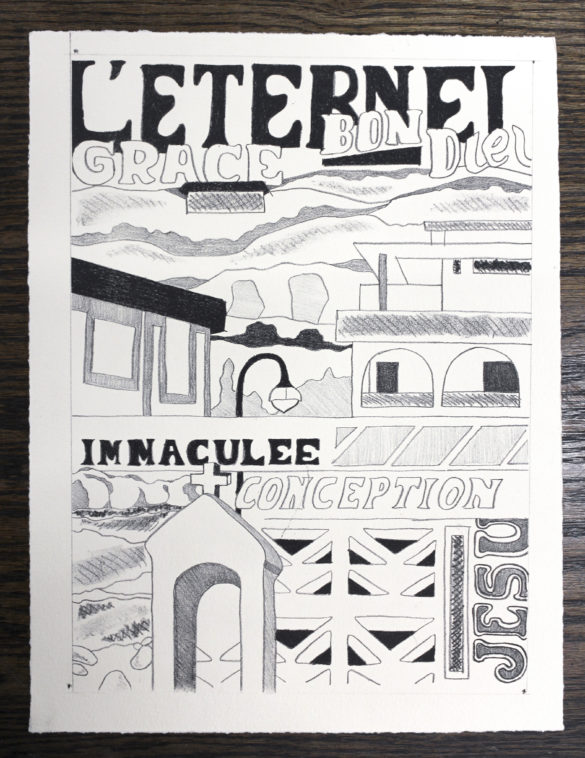

This piece is looking at the architecture in Haiti. Whenever I go to Haiti I look at the tower work, the way the houses are structured, the window sections. The window is sculpted out of the cement—all these different shapes. I find that really interesting because you don’t see these a lot everywhere. This is a distinct style.

MK: Do you have a favorite piece?

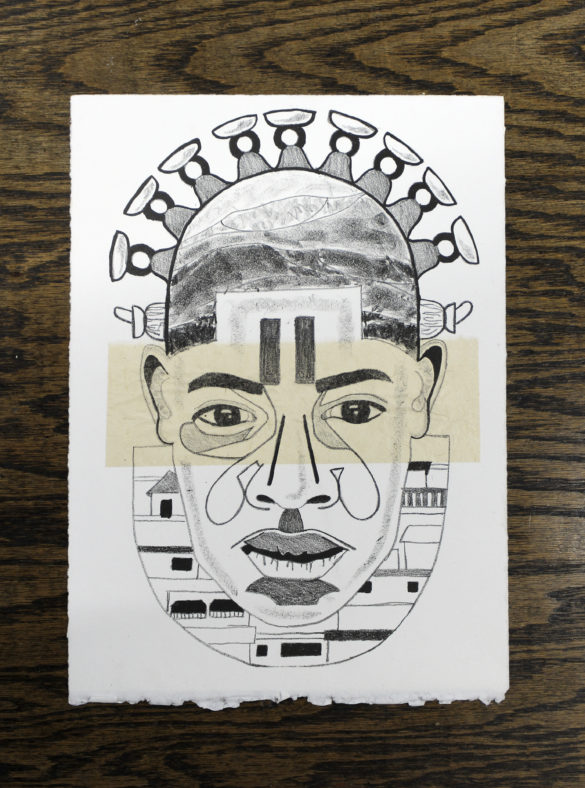

AA: I have to say this one, because it’s all the elements I love in one. This piece is a lithograph. It’s incorporating my face with a well known sculpture from Benin, the Bronze Head of Queen Idia. I also tied in Haiti—I put the mountains in there, I put the women holding the baskets, abstract, on the head, I put the architecture of the houses in there. I’m always finding a way to layer in a little bit of Haitian culture.

MK: Do you have any upcoming shows? If someone wanted to see more of your work, where should they go?

AA: I will be showing some new work at my friend’s event on the 15th of March at Stage Two in Columbia. She has a collective called Synergy, and they’re doing an album release party. It’s an all women hip hop album that she produced. I’m excited about that because, again, I get to show work outside the gallery. The way people talk and the conversations you get to have are different when you’re in different spaces.

And there’s another show in New York at Flux Factory. One of my friends is doing a show for Women’s History Month, for black and brown women. I love artists supporting each other. I’m always down for that.

MK: Is there anything you want to try that you haven’t?

AA: I want to try letterpress, which surprisingly is the one printing technique I haven’t learned. I love words. Why haven’t I tried this? I visited Purgatory Pie Press, a letterpress studio in New York, that does artists’ books, so I was like “collaboration?” and the owners were all for it. I’m really excited. I’ve got a lot of directions, but they all connect in some way.